When I want to hike a less busy trail in mid-summer while still getting great views, I head to Pinnacle Peak Trail at Mt. Rainier National Park. When the mountain is “out” as we say here, there is a stunning panorama of the Paradise Inn and Meadows, the road up from the Nisqually entrance, and the glaciers that stream down the upper half of the peak.

It is stunning. And when the mountain decides not to come “out”? That’s when a foggy or cloudy day brings a chance to notice what is right at my feet as I hike up the 1,150 feet of elevation to the Pinnacle Peak saddle.

Getting to the Trail Head

The trail head is located directly across from Reflection Lakes on Steven’s Canyon Road. There are parking spaces along the road but do be thoughtful about watching for pedestrians and vehicles.

This part of the park can get busy due to the easy walk down to the closest lake. Visitors with limited mobility take full advantage of the well-maintained trail by the lake, and that means that on a sunny day, there are lots of folks about.

You can get to the trailhead from either the Nisqually entrance on State Route 706, the main entrance from the west, or from the Steven’s Canyon Entrance on State Route 123, a lesser frequented area. Do note that the Steven’s Canyon Entrance on the southeast side of the park is only open during the summer months, usually starting in late June.

When the weather looks like it might be sunny, and hopefully clear, I pair this hike in the afternoon with the trail to Bench and Snow Lakes early in the morning. Between hikes, I can sit on the rock wall overlooking Reflection Lakes and eat a bite of lunch before heading up to the saddle, the lowest area between two high mountains, between Pinnacle Peak and Plummer Peak.

Expect to Climb

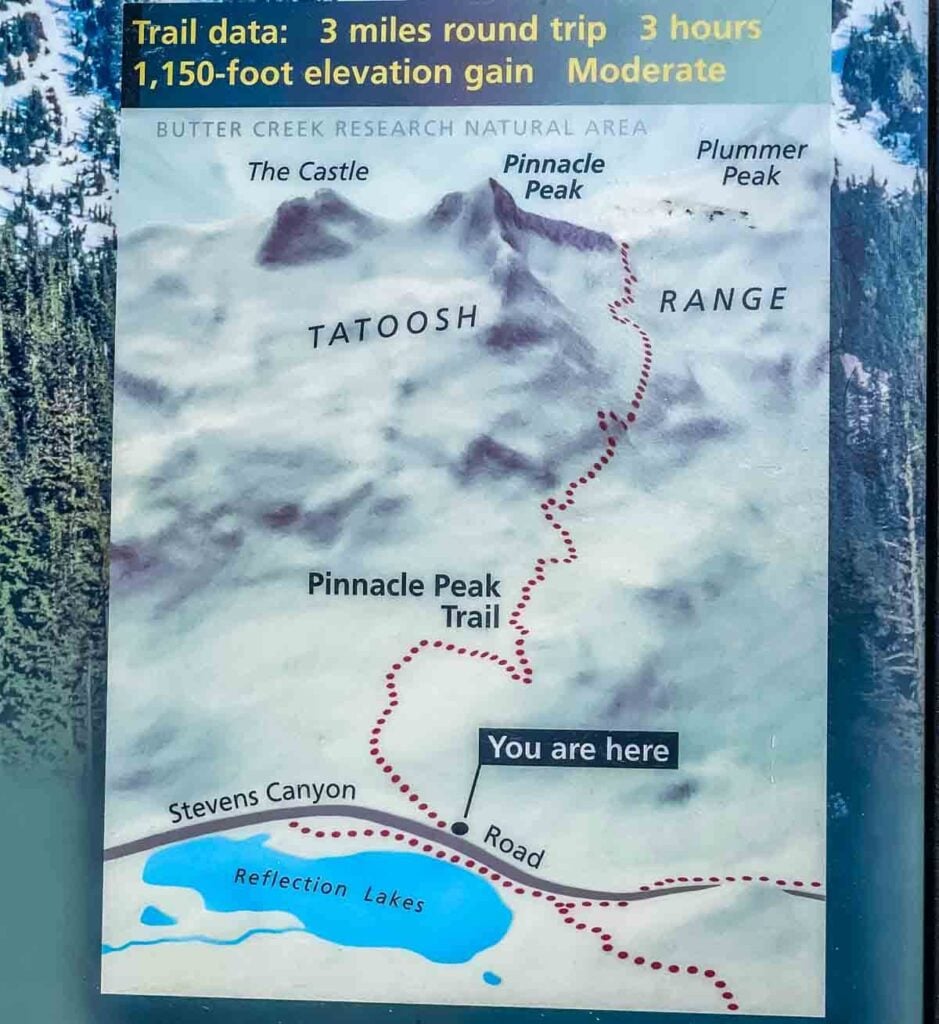

The trail map at the start is a pretty fair representation of the out-and-back up to the saddle just below Pinnacle Peak. Pinnacle is one of several peaks along the top of a ridgeline that makes up this portion of the Tatoosh Mountain Range.

The traditional brown park service trail sign says it is 1.3 miles to the saddle, while the posted map suggests it will be 1.5 miles. The saddle is the end of the maintained trail and is at 5,920 feet. Past the saddle is the Butter Creek Research Natural Area, which is currently restricted to scientists who are monitoring the area, so plan to turn around at the saddle.

Do expect the hike will be a significant climb up and then a steep drop back down. These days, with my wonky knee and barky joints, I expect to stop frequently along the way to take in the views, watch for wildlife, and give myself plenty of chances to rest.

On this sunny day, I spent a solid 3 hours on the trail. It is possible to do the trail faster, especially when heading back downhill, but when Mt. Rainier comes out of the clouds, this is a hike to savor, rather than rush.

Lower Trail Section

The first quarter of a mile on this trail is wide and well maintained, with steps and culverts to allow for walking over streams without getting feet wet.

Family groups are typical here, as even going a short distance up can give some gorgeous views. The voices of children and groups calling to each other echo through the trees.

Because this trail starts at the Reflection Lakes, the start is a popular location for walking just a portion of this trail. Soon enough the trail starts to narrow, while becoming steeper and rockier, and there will be fewer people on trail.

The remainder of the lower section climbs over stairs and up inclined sections of wide gravel that curve around high meadows.

Earlier in the season, snow collects here, and by the end of June there are small ponds that slowly disappear as the summer warms them. Songbirds and small blooms on the heather are abundant. And through the trees, if the clouds dissipate, glimpses of Mt. Rainier peak through the forest.

Wherever the snow melts away, Glacier Lilies bloom in patches of bright white against their green foliage. Here on Mt. Rainer, they are white, with bright yellow centers in each bloom.

This subspecies is sometimes called Idaho Fawn Lily. They grow from bulbs, which are a favorite food for bears as they come out of hibernation. Lilies quickly move through their life cycle, so as the snow melts away at the higher elevations later in the season, fresh patches of lilies bloom. At lower elevations they bloom and are quickly replaced with orange paintbrush as the dominant bloom.

As I climb, I realize I have reached the end of the lower section when the trail becomes fragmented with large rocks and exposed tree roots. Patches of shade become less frequent as the forest begins to thin.

Usually, a breeze picks up about here, and as the openings in the canopy become more frequent, the view of Mt. Rainier makes a stunning appearance.

From here on, Mt. Rainier soars to the north, revealing its more than 14,000-foot peak when the clouds part. This is the spot to sit on the frequent, large trailside rocks and take in the view.

The Paradise Inn and Visitor’s Center at 5,000 feet are easy to spot to the right, at the base of the Paradise Meadows. The terminus of the Nisqually Glacier appears as a giant gash to the center, and above, the vast rock and ice patterns are laid bare on the top 7,000 feet of the mountain. The road back down to the Nisqually Entrance winds away to the left.

The Upper Section

Finally, the trees fall away and open fields of rock rise above and below the trail. Switch backs are the order of the day, and the steep ascent is constant. Loose rock covers the trail, so I’m always glad I’ve got good boots on through here. It is easy to knock rocks loose.

Moving rocks go skittering down, so taking the time to be careful you don’t shower a lower hiker is important. It is a good idea to be aware of the rocks above, as well.

Weather, wind, as well as wildlife passing through can get rocks falling. There is nothing to slow them down, so paying attention is a good idea.

After the last switch back there is a section where a rock wall has been built to shelter the trail. Most of the trail maintenance work in the park is done by volunteers, some organized by the National Park Service, and others part of the Washington Trails Association, as well as other local volunteer groups.

It’s a good spot to pause and reflect on all the work that goes into keeping trails open and as safe as possible for public use.

Pika and Chipmunk

Admittedly, my favorite reason for taking this hike is the prime pika territory on the upper section. Pika live in the avalanche rock fields. They spend the summers “harvesting” grasses and greenery that they then stash away in underground burrows to eat during the long winter.

They dart in and out of the rocks, all the while using their loud “EEP” call to warn other pika of approaching dangers, like hawks and eagles from above or foxes and weasels who hunt the rock fields.

They are active during daylight hours, making them easy to listen for and fun to watch. Sometimes called “rock rabbits,” they are related to rabbits and hares.

Because so much of this trail is above tree line in the rock fall areas, there are plentiful opportunities to watch pika. I stop several times along the way and sit still, listening and watching for them to make an appearance, and on this trail, patience is always rewarded.

This little pika popped out to overlook the area right next to me. A still, quiet human is not a threat, and pikas frequently appear nearby since a close human keeps most small pika predators at bay.

They are also quite territorial, so I have frequently observed them using my presence to sit just above me, take a look around, and vocalize their territorial boundaries to another pika.

Once I reach the saddle, the welcoming committee is always there. Despite the altitude, I am always met by a chipmunk. Yellow Pine Chipmunks enter a state of torpor through the winter, so they are not deterred by the harsh, cold season.

They are fairly common at high altitude in the summer on Mt. Rainier. They also have figured out that hikers rest at the saddle before going back down.

It is important to remember that they are wild animals and should not be fed, no matter how cute they look. Yellow Pine Chipmunks do not build a fat layer for winter. They do have caches of food to get them through the winter, but if we humans are feeding them food that is not good for them all summer long, they are less likely to survive the winter months.

To the south on clear days Mt. St. Helens, Mt. Adams and, sometimes, Mt. Hood are visible from the top of the trail. I am constantly amazed at how even scattered cloud cover will hide these three peaks from view.

On this day, they were well hidden. But that is to be expected when hiking in the Cascade Mountain Range. The ocean to the west and high desert to the east make for unpredictable, changeable weather.

As I turned and started back down the trail, Mt. Rainier soared above me, and I looked forward to variations on this view all the way back to my parked car at Reflection Lakes. In a couple of hours, I would be headed back home, making a stop along the way at the general store at Longmire for a stretch and an ice cream bar.

You may also like: